Geostationary transfer orbit

A geosynchronous transfer orbit or geostationary transfer orbit (GTO) is a Hohmann transfer orbit used to reach geosynchronous or geostationary orbit.[1] It is a highly elliptical Earth orbit with apogee at about 35,700 km, geostationary (GEO) altitude, and an argument of perigee such that apogee occurs on or near the equator. Perigee can be anywhere above the atmosphere, but is usually limited to only a few hundred km to reduce launcher delta-v ( V) requirements and to limit the orbital lifetime of the spent booster.

V) requirements and to limit the orbital lifetime of the spent booster.

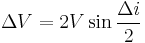

The inclination of a GTO is the angle between the orbit plane and the Earth's equatorial plane. It is determined by the latitude of the launch site and the launch azimuth (direction). The inclination and eccentricity must both be reduced to zero to obtain a geostationary orbit. If only the eccentricity of the orbit is reduced to zero, the result is a geosynchronous orbit. Because the  V required for a plane change is proportional to the instantaneous velocity, the inclination and eccentricity are usually changed together in a single maneuver at apogee where velocity is lowest. The required

V required for a plane change is proportional to the instantaneous velocity, the inclination and eccentricity are usually changed together in a single maneuver at apogee where velocity is lowest. The required  V for an inclination change at either the ascending or descending node of the orbit is calculated as follows:

V for an inclination change at either the ascending or descending node of the orbit is calculated as follows:

For a typical GTO with a semimajor axis of 24,582 km, perigee velocity is 9.88 km/s and apogee velocity is 1.64 km/s, clearly making the inclination change far less costly at apogee. In practice, the inclination change is combined with the orbital circularization (or "apogee kick") burn, so additional  V is required.

V is required.

Even at apogee, the fuel needed to reduce inclination to zero can be significant, giving equatorial launch sites a substantial advantage over those at higher latitudes. Kennedy Space Center is at 28.5 degrees north, the Guiana Space Centre, the Ariane launch facility, is at 5 degrees north latitude and Sea Launch launches from a floating platform directly on the equator in the Pacific Ocean. All have a significant advantage over Russia's high latitude launch sites.

Expendable launchers generally reach GTO directly, but a spacecraft already in a low Earth orbit (LEO) can enter GTO by firing a rocket along its orbital direction to increase its velocity. This is done when a geostationary spacecraft is launched from the space shuttle; a "perigee kick motor" attached to the spacecraft ignites after the shuttle has released it and withdrawn to a safe distance.

Although some launchers can take their payloads all the way to geostationary orbit, most end their missions by releasing their payloads into GTO. The spacecraft and its operator are then responsible for the maneuver into the final geostationary orbit. The five hour coast to first apogee can be longer than the launcher's battery lifetime, and the maneuver is sometimes performed at a later apogee. The solar power available on the spacecraft supports the mission after launcher separation. Also, many launchers now carry several satellites in each launch to reduce overall costs, and this practice simplifies the mission when the payloads may be destined for different orbital positions.

Because of this practice launcher capacity is usually quoted as separated spacecraft mass to GTO, and this number will be higher than the payload that could be delivered directly into GEO.

For example, the capacity (separated spacecraft mass) of the Delta IV Heavy:

- GTO 12,757 kg (185 km x 35,786 km at 27.0 deg inclination), theoretically more than any other currently available launch vehicle (has not flown with such a payload yet)

- GEO 6,276 kg

If the manoeuver from GTO to GEO is to be performed with a single impulse, as with a single solid rocket motor, apogee must occur at an equatorial crossing. This implies an argument of perigee of either 0 or 180 degrees. Because the argument of perigee is slowly perturbed by the oblateness of the Earth, it is usually biased at launch so that it reaches the desired value at the appropriate time. (If the GTO inclination is zero, as with Sea Launch, then this does not apply.)

The preceding discussion has primarily focused on the case where the transfer between LEO and GEO is done with a single intermediate transfer orbit. More complicated trajectories are sometimes used. For example, the Proton M uses a set of four intermediate orbits, requiring five rocket firings, to place a satellite into GEO from the high-inclination site of Baikonur Cosmodrome, in Kazakhstan.[2]